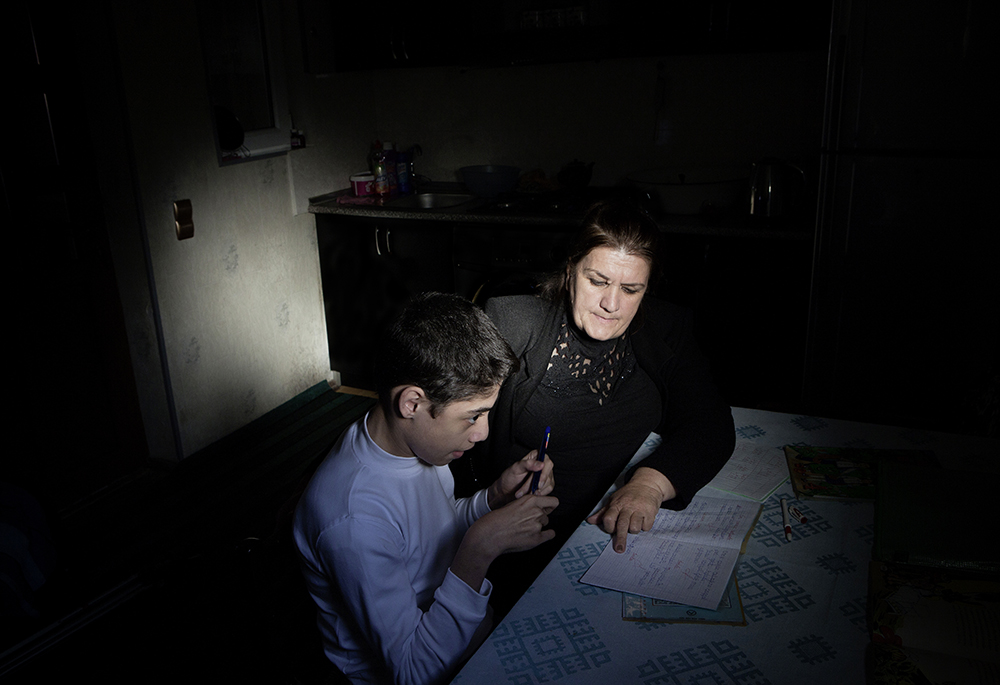

Palmares, Costa Rica

/Photographer: Mónica Quesada Cordero

Year of Submission: 2016 (Educators Edition)

Stars of the Countryside was one of the first Mother-Teacher kindergartens in Costa Rica. Like its counterparts in villages across Panama and Honduras, as well as providing a place where young children play and learn, it also encourages mothers to teach and learn from each other by swapping experiences and know-how. Set up in a village in Palmares, a canton in the south of the country, Stars of the Countryside meets twice a week. Over a meal, its mothers discuss child development, how women can empower themselves and the importance of the right to an education for themselves as well as their children. The organisation behind the kindergartens is Madres Maestras (Mothers Teachers), a Catholic non-profit founded in Panama in 1971. Its motto, “Toda Madre es Maestra” (Every mother is a teacher), adorns the front of tee-shirts handed out to children in Stars of the Countryside.