Standing Rock Reservation & Pine Ridge Reservation, United States of America

/Photographer: Carlotta Cardana

Year of Submission: 2016 (Educators Edition)

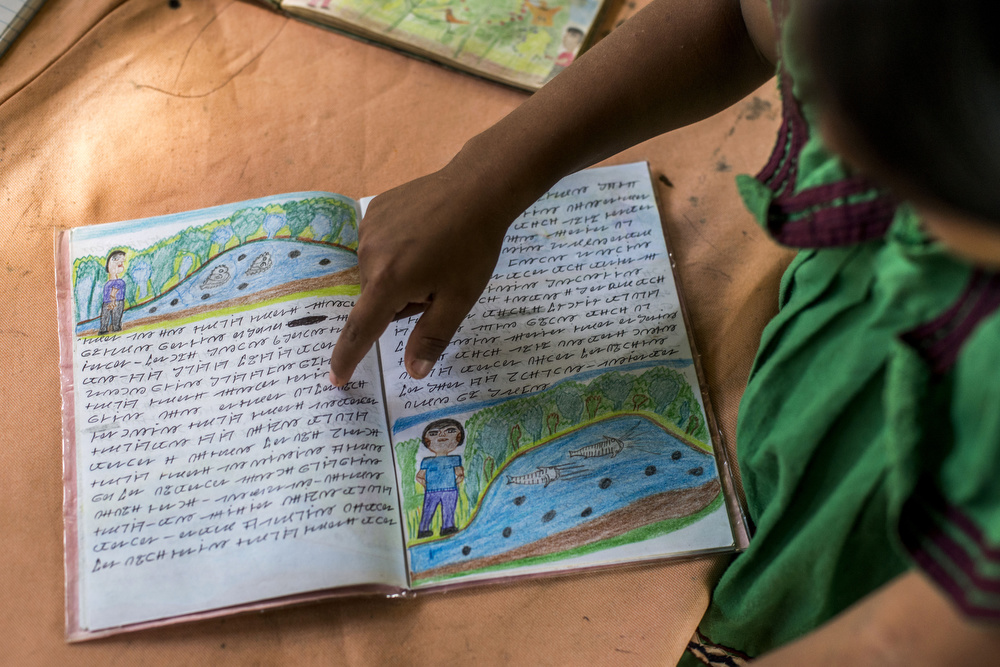

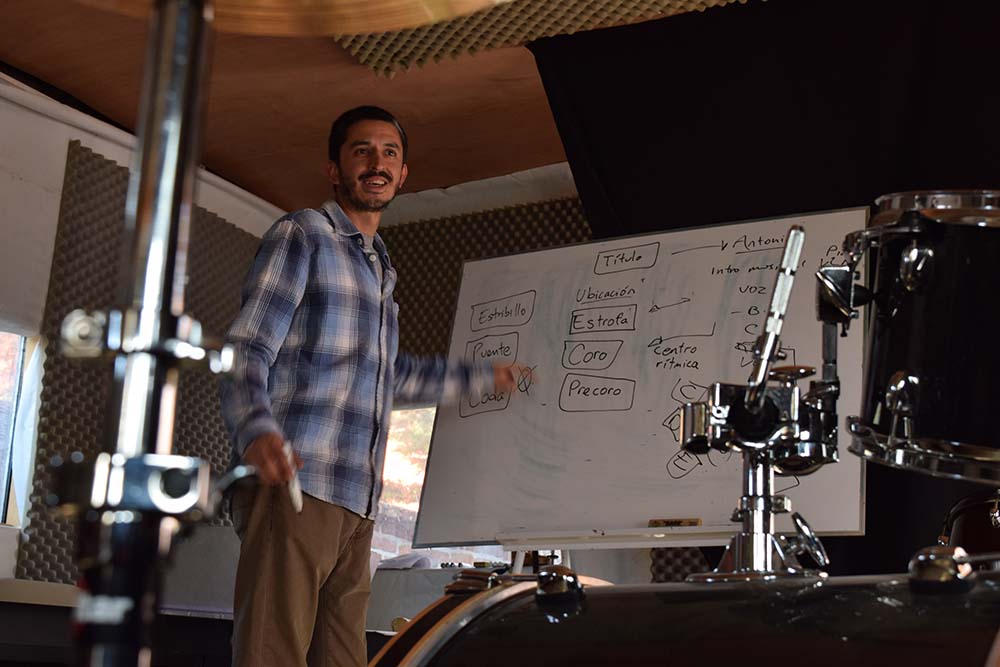

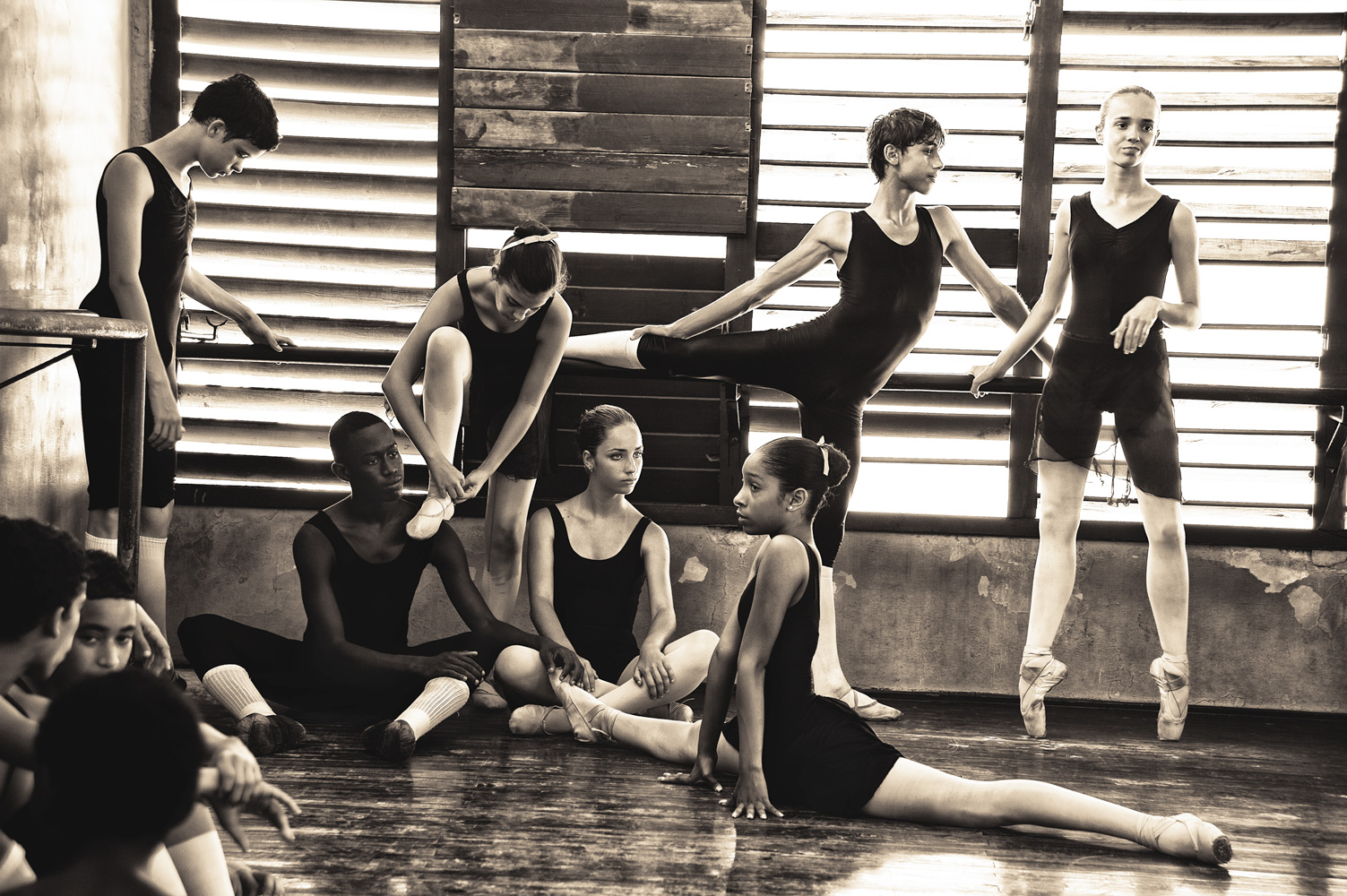

The Lakota are one of the indigenous peoples of North America’s Great Plains region. Today, the biggest concentrations of Lakota are found in South and North Dakota. Young Lakota teachers are keeping their people’s language and culture alive. Maka (near right) teaches Lakota studies to high school juniors and seniors at Red Cloud Indian School, a Jesuit institution in Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. He grew up in Pine Ridge, attending the school where he now teaches. After leaving school in 2005, he set off on a journey that took him first to the University of San Francisco, then to Japan, where he became fascinated with the struggles of the world’s indigenous peoples, and then to New York, where he took a master’s degree in peace and human rights education at Columbia University’s Teachers College. Seven years after leaving home, he returned to Pine Ridge and took up his current job at Red Cloud Indian School. He tells his students it is important to always know who you are culturally as a Native American, but it is also okay to leave your home, get an education and experience the world. Típiziwiŋ (far right) learns and teaches the Lakota language to her community in Standing Rock Reservation, on the borders of North and South Dakota. Until recently, Lakota looked like it would become another of the hundreds of extinct North American languages. To help it survive, Típiziwiŋ launched the Lakota Language Nest, a language immersion programme for pre-school children. For eight hours a day, a group of three- to five-yearolds heard and spoke only Lakota. By the end of the course, they were Standing Rock’s first child speakers of the language for more than fifty years.