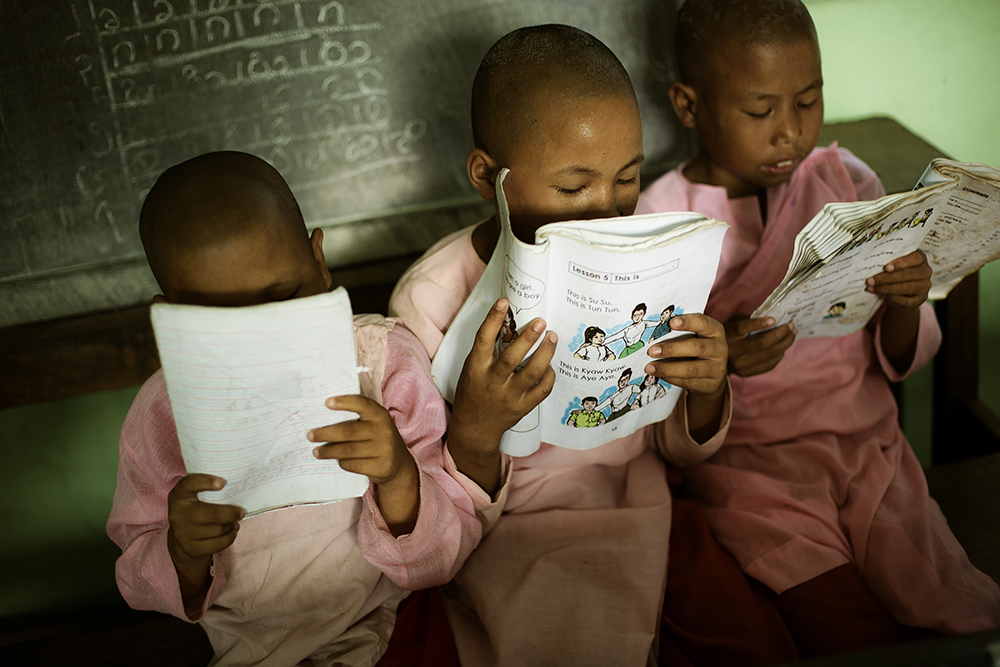

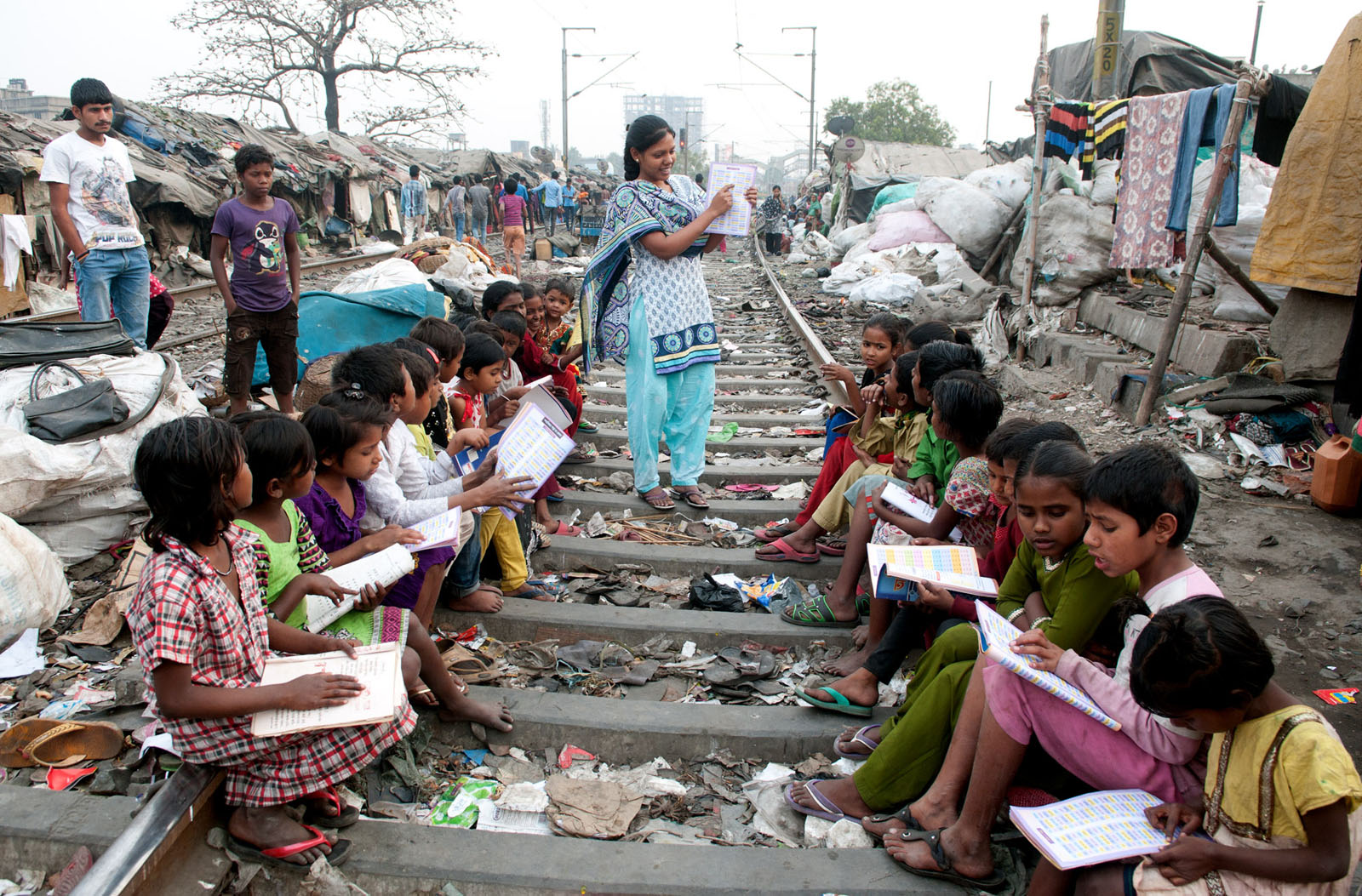

Bum Nua, Vietnam

/Photographer: Annie Griffiths

Year of Submission: 2016 (Educators Edition)

In Bum Nua, a remote region of north-west Vietnam near the border with Laos and China, a visiting teacher leads an exercise class for a group of La Hu children. The teacher has been trained as part of a project run by Church World Service, an organisation backed by 37 Christian communities from around the world. The project’s main goal is to raise teaching standards in under-served communities. Project staff also work with mothers, helping them gain a better understanding of the importance of hygiene, sanitation and nutrition. Originally from a region on the Tibetan plateau, the La Hu migrated southwards into China and south-east Asia around two hundred years ago. Today, around 9,000 La Hu live in Vietnam, a tiny number compared with the more than 700,000 who live across the border in China’s Yunnan province.