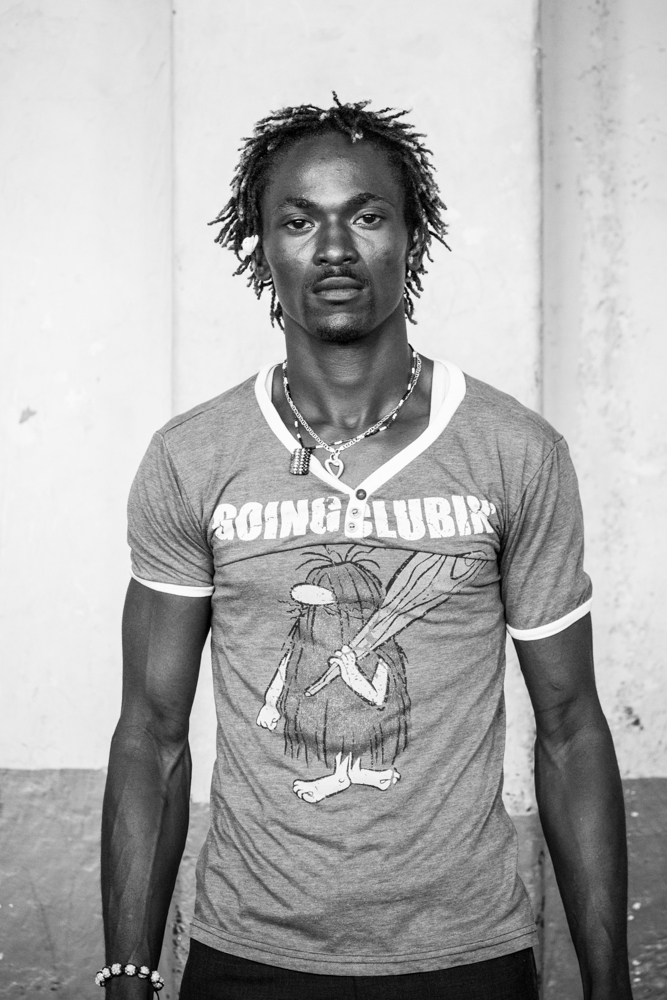

Harare, Zimbabwe

/Photographer: Nyadzombe Nyampenza

Year of Submission: 2016 (Educators Edition)

Chikonzero Chazunguza is a visual artist who runs Dzimbanhete Arts Interactions, an arts and culture resource centre that promotes Zimbabwean and African culture. Since its opening in 2005, Chiko’s centre – which takes its name from the Shona word for light footstep – has hosted workshops, exhibitions, performances and a host of other arts programmes and projects. The centre’s recent projects include organising its first Mbira Sunsplash festival in 2014 to promote consciousness through culture and building an All Africa Village to show the range of architectural styles found in villages across Africa. Chiko’s own work ranges from multimedia and performance pieces to paintings, prints and installations, much of it challenging what he sees as the degradation of indigenous spirituality and traditional forms of order